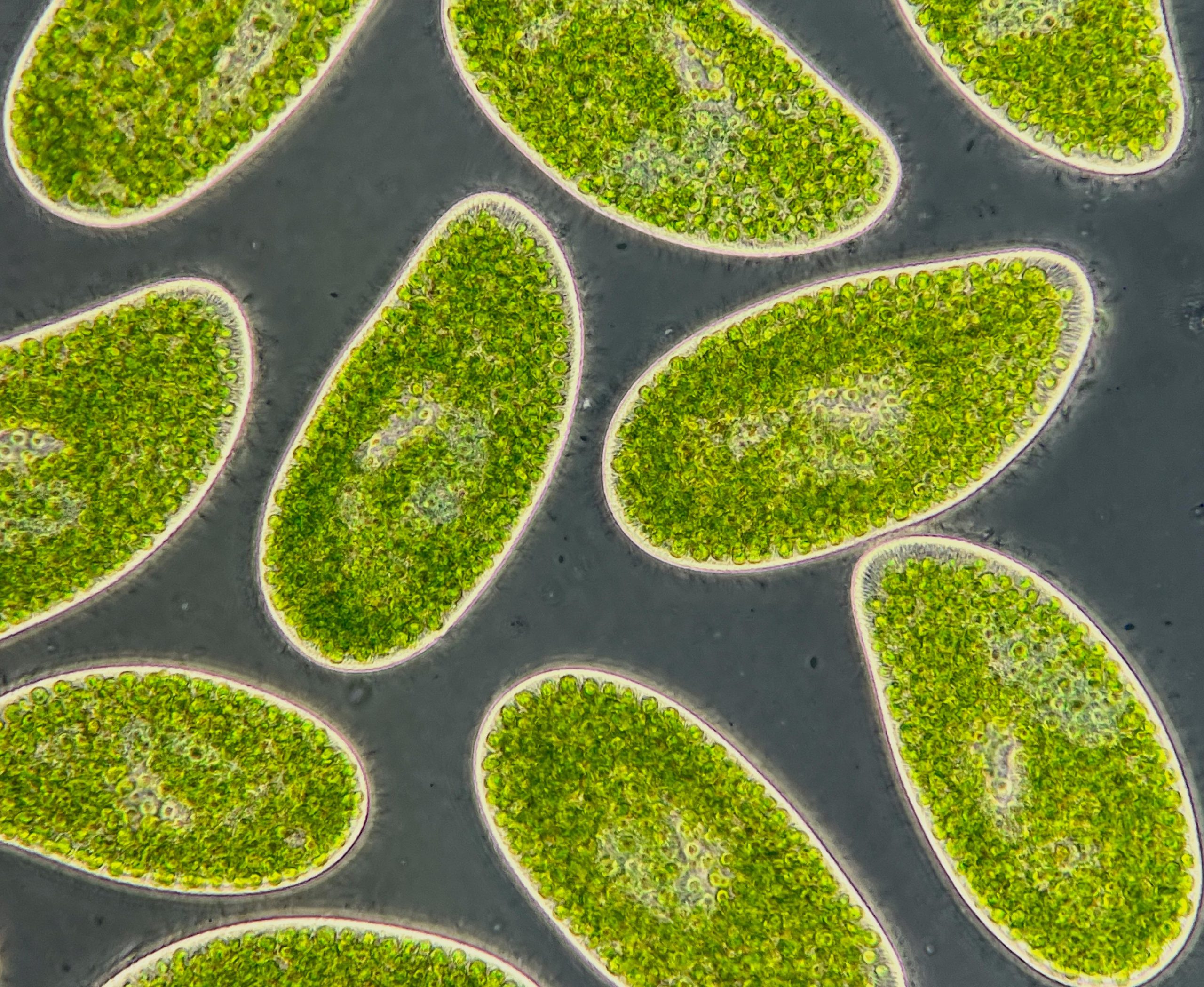

Једноћелијска бића попут ових налазе се у језерима и рекама широм света Парамециум бурсариа Може и да једе и да фотосинтетише. Микроби попут ових играју двоструку улогу у климатским променама, ослобађајући или апсорбујући угљен-диоксид – гас стаклене баште који задржава топлоту и који је главни покретач загревања – у зависности од тога да ли усвајају животни стил налик животињама или биљкама. Заслуге: Даниел Ј Вицзински, Универзитет Дуке

Повећање нивоа топлоте могло би да гурне океански планктон и друге једноћелијске организме ка прагу угљеника, што би могло да погорша глобално загревање. Међутим, недавне студије сугеришу да је могуће идентификовати ране знаке упозорења пре него што ови организми достигну ту критичну тачку.

Група научника која спроводи истраживања о широко распрострањеној, али често занемареној класи микроба, открила је петљу повратне информације о клими која би могла да појача глобално загревање. Међутим, овај налаз долази са позитивне стране: може бити и рани сигнал упозорења.

Користећи компјутерске симулације, истраживачи са Универзитета Дуке и Универзитета у Калифорнији у Санта Барбари показали су да велика већина глобалног океанског планктона, заједно са многим једноћелијским организмима који насељавају језера, тресетишта и друге екосистеме, можда достиже врхунац. тачка. Овде, уместо да апсорбују угљен-диоксид, почињу да раде супротно. Ова промена је резултат начина на који ваш метаболизам реагује на загревање.

Пошто је угљен-диоксид гас стаклене баште, ово заузврат може подићи температуре – позитивна повратна спрега која може довести до брзих промена, где мале количине загревања имају велики утицај.

Али пажљивим праћењем њиховог обиља, можда ћемо моћи да предвидимо прекретницу пре него што она стигне, извјештавају истраживачи у студији објављеној 1. јуна у часопису Натуре. функционална екологија.

У новој студији, истраживачи су се фокусирали на групу микроорганизама званих миксотрофи, названи тако јер мешају два начина метаболизма: могу фотосинтетизирати као биљка или ловити храну као животиња, у зависности од услова.

„Они су као[{“ attribute=““>Venus fly traps of the microbial world,” said first author Daniel Wieczynski, a postdoctoral associate at Duke.

During photosynthesis, they soak up carbon dioxide, a heat-trapping greenhouse gas. And when they eat, they release carbon dioxide. These versatile organisms aren’t considered in most models of global warming, yet they play an important role in regulating climate, said senior author Jean P. Gibert of Duke.

Most of the plankton in the ocean — things like diatoms, dinoflagellates — are mixotrophs. They’re also common in lakes, peatlands, in damp soils, and beneath fallen leaves.

“If you were to go to the nearest pond or lake and scoop a cup of water and put it under a microscope, you’d likely find thousands or even millions of mixotrophic microbes swimming around,” Wieczynski said.

“Because mixotrophs can both capture and emit carbon dioxide, they’re like ‘switches’ that could either help reduce climate change or make it worse,” said co-author Holly Moeller, an assistant professor at the University of California, Santa Barbara.

To understand how these impacts might scale up, the researchers developed a mathematical model to predict how mixotrophs might shift between different modes of metabolism as the climate continues to warm.

The researchers ran their models using a 4-degree span of temperatures, from 19 to 23 degrees Celsius (66-73 degrees Fahrenheit). Global temperatures are likely to surge 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels within the next five years, and are on pace to breach 2 to 4 degrees before the end of this century.

The analysis showed that the warmer it gets, the more mixotrophs rely on eating food rather than making their own via photosynthesis. As they do, they shift the balance between carbon in and carbon out.

The models suggest that, eventually, we could see these microbes reach a tipping point — a threshold beyond which they suddenly flip from carbon sink to carbon source, having a net warming effect instead of a cooling one.

This tipping point is hard to undo. Once they cross that threshold, it would take significant cooling — more than one degree Celsius — to restore their cooling effects, the findings suggest.

But it’s not all bad news, the researchers said. Their results also suggest that it may be possible to spot these shifts in advance, if we watch out for changes in mixotroph abundance over time.

“Right before a tipping point, their abundances suddenly start to fluctuate wildly,” Wieczynski said. “If you went out in nature and you saw a sudden change from relatively steady abundances to rapid fluctuations, you would know it’s coming.”

Whether the early warning signal is detectable, however, may depend on another key factor revealed by the study: nutrient pollution.

Discharges from wastewater treatment facilities and runoff from farms and lawns laced with chemical fertilizers and animal waste can send nutrients like nitrate and phosphate into lakes and streams and coastal waters.

When Wieczynski and his colleagues included higher amounts of such nutrients in their models, they found that the range of temperatures over which the telltale fluctuations occur starts to shrink until eventually the signal disappears and the tipping point arrives with no apparent warning.

The predictions of the model still need to be verified with real-world observations, but they “highlight the value of investing in early detection,” Moeller said.

“Tipping points can be short-lived, and thus hard to catch,” Gibert said. “This paper provides us with a search image, something to look out for, and makes those tipping points — as fleeting as they may be — more likely to be found.”

Reference: “Mixotrophic microbes create carbon tipping points under warming” by Daniel J. Wieczynski, Holly V. Moeller and Jean P. Gibert, 31 May 2023, Functional Ecology.

DOI: 10.1111/1365-2435.14350

The study was funded by the Simons Foundation, the National Science Foundation, and the U.S. Department of Energy.

„Љубитељ пива. Предан научник поп културе. Нинџа кафе. Зли љубитељ зомбија. Организатор.“

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25594197/Genki_TurboCharger_Hero.jpg)

More Stories

Када ће астронаути лансирати?

Према фосилима, праисторијску морску краву појели су крокодил и ајкула

Федерална управа за ваздухопловство захтева истрагу о неуспешном слетању ракете Фалцон 9 компаније СпацеКс